Vibrant Animal health apparatus | economic growth | social well being | food security | Reduction of resource-based hurdles|

Prepared by: Dr. Farhan Ahmed Yusuf | Senior Livestock Consultant |Holistic Livestock Solutions |

🗓️ 7th December 2025

Prologue:

Animal health services, which ultimately seek to control animal diseases, generally include: (i) the provision of veterinary care for animals; (ii) the distribution of veterinary medicinal products; and (iii) advice and training for farmers. Thus, the prevention and control of animal diseases with a view to the economic development of livestock production industries do fall within the sovereign duties.

The delivery of services in the field of animal health therefore involves a large number of stakeholders, from the private and public veterinary sectors, together comprising the Veterinary Services. The ultimate gist is the establishment and operationalization of a multi-stakeholder animal health system that enables all livestock farmers, especially the poorest, to have access to quality animal health care services that are: (1) sustainable; (2) carried out by competent persons; (3) conveniently located; (4) financially affordable; (5) using effective veterinary inputs; and (6) ultimately, in compliance with professional ethics, standards.

Farmers often notice the obvious losses first, a dead animal, a sudden dip in herd size, but the real damage from poor animal health is quiet, gradual and far more costly. It shows up as milk that never reaches the milk pail, weight that never accumulates on the scale, eggs that are smaller or fewer and young animals that grow slowly. The system encounters costly cyclic inefficiencies. This article walks you through that hidden drain, explains how to find it and shows a simple, risk-based way to stop the leak before it wrecks your business.

This article explores how these structural challenges unfold, why they matter and what it takes to build a resilient, competitive livestock sector that can sustain both livelihoods and export growth.

A weak animal-health apparatus can unleash a formidable havoc across livestock systems, a slow-burning harm born from cracks and loopholes within the health setup itself. Its damage can run deep, slicing through farm-level micro-economics and rippling upward to shake national macro-economic stability, If the animal-health system is not fully resourced. Yet these loopholes and the losses they create are entirely preventable.

Consequences

When a country’s animal-health apparatus is under-resourced, the effects reach far beyond the farm. Over time, vital sectors receive lower investment, as both domestic and foreign investors shy away from industries vulnerable to losses. The economy experiences inflationary pressures, food insecurity and volatile food prices become a direct threat to the poor, often triggering social unrest. The country loses the opportunity to earn foreign hard currency, which is crucial for purchasing the imported inputs.

Policy becomes inactive or reactive, unable to stimulate economic activity effectively. Unemployment and underemployment rise sharply, forcing bright graduates and budding entrepreneurs to seek opportunities abroad, creating a cycle of persistent national vulnerability.

Where the money goes when animals fall ill

When an animal gets sick, we think about medicines and vet visits and rightly so. But the bigger, more pernicious losses are less visible: reduced production, wasted feed, lowered fertility and productivity that never fully recovers. Imagine a dairy goat losing half a litre a day for a month, that loss looks small day-to-day, but becomes serious over time. The same is true for a flock of hens whose feed conversion becomes poor for a few weeks: feed costs rise and egg output drops and the result is an invisible monthly bill.

This is why we must move beyond thinking of disease as only a veterinary problem and start thinking of poor health as a business problem and the next section explains how to identify the biggest drains so you can prioritize actions that buy the most benefit.

Under-resourced animal health apparatus shakes a nation’s Macroeconomy. A weak animal-health system may seem like a local problem at first, but these small cracks quietly drain rural incomes and reduce national livestock output, creating ripple effects on the macro-economy.

As production falls, food prices rise, imports increase and the economy loses foreign exchange. Disease outbreaks spread faster, trade bans hit exports and investors pull back from meat, dairy and feed sectors. Governments scramble to cover emergency costs, diverting funds from development. Jobs disappear across the value chain, poverty grows and food insecurity rises.

All this begins with one root cause: an under-resourced animal-health system. What looks like a veterinary problem is, in reality, a vulnerability to the macroeconomy, entirely preventable with proper planning, funding and early action.

Finding the top leaks: how to identify the biggest threats on your farm

You can’t fix what you don’t measure. Start by asking three questions: which diseases or problems happen most often on my farm, which cause the greatest drop in productivity and which are easiest to prevent? The answers form your “top three”, the threats you will manage most aggressively.

Look for patterns in simple records: milk per day, number of eggs per hen, weight gain of young stock and feed and water consumed. These are your early-warning sensors. For example, a steady fall in milk over a week, or a small but continuous drop in feed intake for several animals, is often the first sign of trouble, long before animals look obviously sick. Once you identify the top three threats (parasites, a recurring mastitis problem, or poor ventilation causing respiratory stress, for instance), you can move from guessing to targeted action, which is far more efficient. The next section shows how to translate those priorities into a risk-based plan.

Building a risk-based plan that protects profit, not just animals

Risk-based management focuses on three steps: identify, rank and control. First, list the likely problems (using the patterns you found earlier). Second, rank them by impact on income, not just how many animals get sick, but how much each problem reduces milk, weight, reproduction, or survival. Third, choose prevention steps that reduce the risk of those top problems.

This is not complicated: vaccinate against the high-impact disease, tighten feed storage where feed mould is causing chronic poor growth, improve drainage in wet yards where foot problems start. Prioritizing in this way means your limited money, labour and attention deliver the biggest returns. To understand why prevention saves money, read the real-world examples in the next section.

Real farms, real numbers: examples that show the calculus

The value of risk-based prevention becomes clear when we put numbers to the problems.

Example 1, young goats and coccidiosis: A herd loses growth in 36 kids and loses 4 to death. Treatment and growth setbacks cost several hundred dollars, while a focused prevention plan (better hygiene, anticoccidial medication at risk periods) costs a fraction of that and avoids the loss.

Example 2, layers in poorly ventilated housing: A 10% drop in egg production across a flock of 500 is a constant monthly loss. A one-time low-cost intervention, improving airflow and removing damp litter, often restores production quickly and pays back many times over.

Example 3, mastitis in a dairy animal: A temporary drop in milk for a single cow can erase weeks of profit. Simple, repeated small habits (clean teat cloths, correct milking order, post-milking teat disinfection) cost little but prevent recurring losses.

Small Drop, Big Loss: The Cost of 10% Less Eggs

A mother farmer in Somaliland has 35-layer hens, selling each egg for $0.19. Her hens produce about 33 eggs daily, earning roughly $6.11/day,covering family expenses.

Then came a 10% drop in production, just 3 fewer eggs per day. The result? Daily income fell to $5.56, a loss of $0.56/day. Over a month, this adds up to $16.67, money that could have gone to feed, veterinary care, or reinvestment.

Lesson: Even a small drop in egg production can hit small-scale farmers hard. Consistent care, proper feeding and disease prevention aren’t luxuries, they’re the difference between profit and loss.

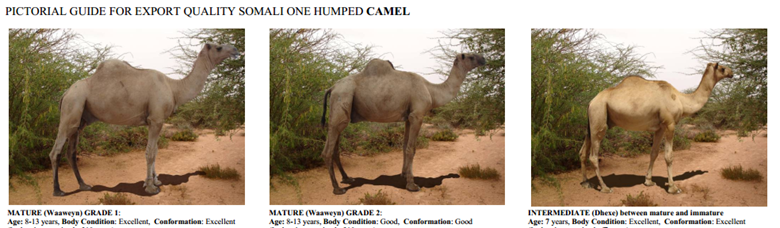

In 2012, For example, 3,505,050 heads of live animals were exported from the Port of Berbera whose value is equivalent to $ 493,519,790 in contrary to that, in 2017, the country exported 1,400,000 only, indicating a sharp decline in export volumes over five years. The reasons are multi-faceted, can be natural challenges, inefficiencies, external shocks such as market fluctuations and changing trade policies affecting export procedures and requirements.

These examples show that prevention is not an expense, it is an investment that compounds. If you want to design the actual interventions for your farm, the next section gives the practical checklist.

A practical prevention checklist you can use this week

Turn insights into routine actions. Here is a short checklist that links directly to the risks you identified:

- Record baseline production numbers (milk, eggs, weight gains) weekly.

- Establish a vaccination and deworming calendar matching age groups and local disease risks.

- Improve feed storage: – clean, dry, rodent-free stores prevent mould and mycotoxin problems.

- Keep water clean and measure consumption, drops are early warnings.

- Improve housing ventilation and drainage to reduce respiratory and hoof problems.

- Enforce a simple biosecurity gate: clean boots, limit visitors and isolate new or sick animals.

- Train one worker or family member to spot the five early-warning signs: reduced feed intake, lower milk, isolation, dull coat and fast breathing.

These actions are linked, better feed storage reduces chronic poor growth (checklist item 3), which reduces susceptibility to parasites (item 2), which reduces production loss that shows up in your weekly records (item 1). Small routines reinforce each other. The next section explains how to detect problems early so those routines remain effective.

Detect early, act fast: early-warning signs and simple measures

The majority of big losses can be avoided by spotting small changes. Early warning comes from daily observation and simple metrics:

- Feed intake: place a daily or weekly feed bowl check and note if animals leave more feed than usual.

- Water use: mark a baseline for water consumed by groups; a 10–20% drop is meaningful.

- Milk check: record each milking and flag more than a 10% drop.

- Behaviour: animals that separate from the group or move slowly need attention.

- Appearance: coat condition, eye clarity and breathing rate all tell a story.

When you detect one of these signals, act with a short, defined response: isolate the animal, check temperature and appetite, treat common causes (e.g., worms, sour milk, bloat) with the low-cost first-line options on your farm plan and if no improvement in 24–48 hours, consult your vet. Acting early keeps treatment costs low and limits production losses. The next section looks at measuring return on prevention so you can prove the value to yourself and fund future improvements.

Measuring success: how to show prevention pays

Farmers should be able to answer two simple questions each month: did my output improve, and did my costs fall or remain controlled? Use the baseline records to track progress:

- Milk per animal per day — target recovery to baseline after interventions.

- Feed cost per kg of product — watch for improvements as sick animals recover.

- Mortality and reproductive rates — small improvements here compound to large financial benefits.

A simple monthly review comparing this month to the baseline will show whether your actions are working. If an intervention costs $100 but prevents a $600 loss (as in the coccidiosis example), you have clear proof to expand that intervention farm-wide. The final section wraps the approach into practical advice for the farmer who’s ready to change.

From knowledge to habit: how to make risk-based management part of daily farm life

Ideas change nothing unless they become habits. Build short checklists into daily routines and make one person accountable for the “metrics table” (milk, feed, water, deaths). Use simple tools, a whiteboard, a notebook, or a mobile note app and review weekly. Start with the top three risks, get them under control, then add the next three.

Remember these guiding principles: prevention protects profit; small, regular actions beat rare, expensive fixes; and measurement guides decisions. If you follow the steps described, identify, rank, control, detect early and measure, you transform animal health from a cost centre into a profit protection strategy.

Final thought: treat animal health as a financial plan

When disease becomes a line in your budget rather than a crisis, you gain control. Risk-based management is a way to turn uncertainty into predictable outcomes. It requires curiosity, simple record-keeping and the discipline to act early. The reward is measurable: healthier animals, steadier production and a farm business that keeps the money you worked so hard to earn.

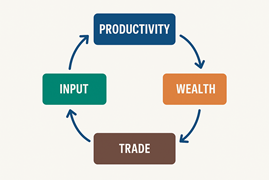

Making strategic Choices – Strategic Funding and System Options

A risk-based animal health apparatus requires adequate resources and inputs to operate effectively. When well-supported, it enhances livestock productivity, stabilizes wealth for farmers and enables trade of high-quality livestock products that can fetch premium prices.

A weak animal-health apparatus not only threatens farm-level productivity but also undermines national economic stability. Strengthening this system requires sustainable financing, strategic investment and innovative service delivery. Several workable approaches can help achieve these goals:

1. Export Deduction Approach

Allocating a small fee per exported animal is a practical way to generate dedicated funds. For example, a $2 deduction per animal from the 4 million livestock exported annually would generate $8 million each year, which could be injected into veterinary services. These resources can strengthen disease prevention, improve productivity and ultimately increase export earnings.

2. National Livestock Development Fund

A National Livestock Development Fund could be established to finance vital services, including infrastructure, veterinary systems, disease surveillance and diagnostic capabilities. Such a fund ensures sustainable financing to support the growth of the livestock sector, safeguard animal health and enhance economic stability.

3. Capital Seed Fund

Devising a capital seed fund is another viable option. By strategically investing initial resources, the fund can build the backbone of the animal-health system from diagnostic laboratories to trained personnel while generating substantial returns through improved productivity, healthier herds and higher export earnings.

4. Veterinary Privatization

Partial privatization of veterinary services can complement the current public-led system. Encouraging private sector participation enhances efficiency, accessibility and responsiveness in veterinary care, disease surveillance and diagnostic services, while reducing the burden on public resources.

5. Empowering Producers and Expanding Value-Added Livestock Products

The countries in the Greater Horn of Africa (GHoA) need to appropriate substantial investments into building the infrastructure required for a modern, competitive, livestock-based economy. When properly developed, this sector can complement other income sources, attract additional investors and strengthen the livestock processing segment, generating broader economic growth. Such development empowers people to become producers of their own food and income while stimulating the export of value-added livestock products alongside the live animal export industry. This may reduce the burden created by an undiversified livestock economy and its under-specialized segments, paving the way for stronger, multi-pronged livestock value chains that are more resilient and competitive.

6. Building a Financial Infrastructure

As there is a notable dearth of Letters of Credit (LCs), In Somaliland, many individuals and businesses face significant challenges when transferring money internationally due to the lack of a direct banking wire system. Due to limited financial infrastructure, local banks cannot directly send or receive international payments because they lack access to global banking networks, they are dependent on intermediary banks. Intermediary banks often complicate transactions, causing delays, added costs and uncertainty. This bottleneck not only affects everyday payments but also impacts businesses, including livestock traders and agribusiness entrepreneurs, ultimately influencing the broader macroeconomy.

for Somaliland to compete in a modern, fast-moving economy, it must invest in a credible financial infrastructure. Such a system would ease access to the global marketplace, strengthen investor confidence and enable seamless participation in digital trade. Reliable payment systems, digital banking solutions, cross-border transaction channels and transparent financial regulations are essential components.

A strong financial infrastructure not only supports livestock exporters in receiving secure payments from international buyers, but also empowers local entrepreneurs to market value-added livestock products online. By modernizing financial systems, Somaliland can unlock new economic opportunities, attract global partnerships and ensure the livestock sector grows in step with global trade trends. This may also include establishing reliable payment gateway systems to support digital marketplaces and facilitate secure online transactions for livestock and value-added product.

This article is prepared by Holistic Livestock Solutions (HLS) for open technical notes and inputs for our esteemed readers.